Neighborhoods in Transition: Who Decides Our Future?

By Bill Ellig, University Heights Resident and Uptown Planners Board Member emeritus

The 1925 Craftsman Bungalow at 4222 Georgia Street will be replaced by the Georgia Modern with 5 Stories, 31 units, and 2 parking spaces

If you live in Normal Heights, North Park, or University Heights, you may be wondering why and how so many tall, dense buildings are being constructed in our neighborhoods with minimal public review.

For example, both the “Georgia Modern” building above and “The Winslow” project below have been permitted by the City without review by the North Park Planning Group. The Winslow project is already under construction.

The Winslow, 4353 Park Blvd., 7 stories, 379 units, 500 parking spaces

All of this construction is part of a statewide and local effort to increase the supply of housing, particularly for very low, low, and moderate-income households.

However, in the City’s and State’s rush to dramatically increase the supply of housing in a short period of time, changes to Municipal Code have been implemented which circumvent adopted Community Plans and bypass the usual channels of community input.

While some community members applaud these efforts to increase the supply of housing for any income level, others are concerned about the proliferation of housing in their neighborhoods without parking, design review, or community knowledge or input. Further, many of these projects are not targeted to very low, low, or moderate-income households.

This article will attempt to provide a brief overview of how land use planning is structured in San Diego, a history of planning in San Diego, and recent State and local changes that are dramatically changing how and where development can occur in our neighborhoods.

How Land Use Planning is Organized in the City of San Diego

Land use planning in the City of San Diego is guided by the General Plan, Community Plan, and the Municipal Code which specifies zoning details. It is important to note that if there are conflicts between the General Plan, Community Plans, and Municipal Code, the Municipal Code takes precedence.

The San Diego General Plan

The process begins with the General Plan of the City of San Diego. According to the City’s website, “The City's General Plan is its constitution for development. It is comprised of 10 elements that provide a comprehensive slate of citywide policies and further the City of Villages smart growth strategy for growth and development.”

General Plan elements include Land Use and Community Planning, Mobility, Urban Design, Economic Prosperity, Public Facilities, Noise, and Historic Preservation.

Community Plans

The City is comprised of 52 Community Plan Areas that divide up the city. Each area has its own Community Plan with a set of elements similar to the General Plan but more specific to its plan area.

City of San Diego Community Plan Area Map

The Community Plan Land Use Element identifies the location of residential, commercial, and mixed-use areas and also defines how many residential units that can be built on an acre of land. As a reference, the typical lot size in University Heights is about 50 feet x 150 feet or .17 acre. Examples of Community Plan Land Use categories are:

Residential-Low (single family homes): 5-9 dwelling units per Acre (DU/AC)

Residential-Medium: 16-29 DU/AC

Residential-Very High: 74-109 DU/AC

In addition, the Community Plan Urban Design Element “guides future development to ensure that the physical attributes that make Uptown unique will be retained and enhanced by design that responds to the community’s particular context—its physical setting, market strengths, cultural and social amenities, and historical assets while acknowledging the potential for positive growth and change.”

Municipal Code Zones

Underlying the Community Plans are the Zones defined in the San Diego Municipal Code which “help ensure that land uses within the City are properly located and that adequate space is provided for each type of development identified. Base zones are intended to regulate uses; to minimize the adverse impacts of these uses; to regulate the zone density and intensity; to regulate the size of buildings; and to classify, regulate, and address the relationships of uses of land and buildings.” The Municipal Code further specifies the height, density, setbacks, and other details of construction in each zone.

At left is detail from the Land Use Map from the 2016 Uptown community Plan. At right is the Zoning Map for the same area.

For example, the Residential-Medium Land Use category defined in the Community Plan is translated into the associated Base Zone RM-2-5 in the Municipal Code. This zone allows up to 29 units per acre, requires a setback from the property line of at least 15 feet, and sets a maximum height of 40 feet. There are many other specifications as well.

Overview of the City of San Diego Construction Permit Process

The City of San Diego Development Services Department (DSD) requires a permit for projects such as new construction, additions, remodeling, or repairs to electrical, mechanical and plumbing systems.

DSD will evaluate the project to see if it conforms to the zoning and other applicable Municipal Code regulations. If it does, the project will be approved “ministerially” without any public input.

As opposed to “Ministerial Review”, some projects are subject to “Discretionary Review” which requires “a decision-maker to exercise judgment and deliberation.” Common reasons for discretionary review include proposals that:

Deviate from zoning requirements. For example, a proposed building may exceed the height or density limits prescribed by zoning.

Involve historical or potentially historic resources. Proposals that include structures over 45 years old are subject to Potential Historical Resource Review.

Modify a previously conforming use

Are located in environmentally sensitive lands

Are located in the Coastal Zone

Historically-Designated Home, 4407 Georgia Street

Discretionary approvals are granted at the discretion of a City decision-maker and may require a public hearing by a Community Planning Group, the Historical Resources Board, Planning Commission, and/or the City Council. These are public meetings where the community may provide input on proposed projects.

The City Council is elected by the voters. The Planning Commission and the Historical Resources Board are nominated by the Mayor and approved by the City Council. The Community Planning Group members are elected by residents, business owners or their representative in the Community Planning Area. It is important to understand that Community Planning Groups are only an advisory board to the City. They do not decide, they just recommend.

Ultimately the City makes the determination to grant or deny a construction permit.

A Brief History of Planning in San Diego

Urban Planning Begins in the Early 1900s

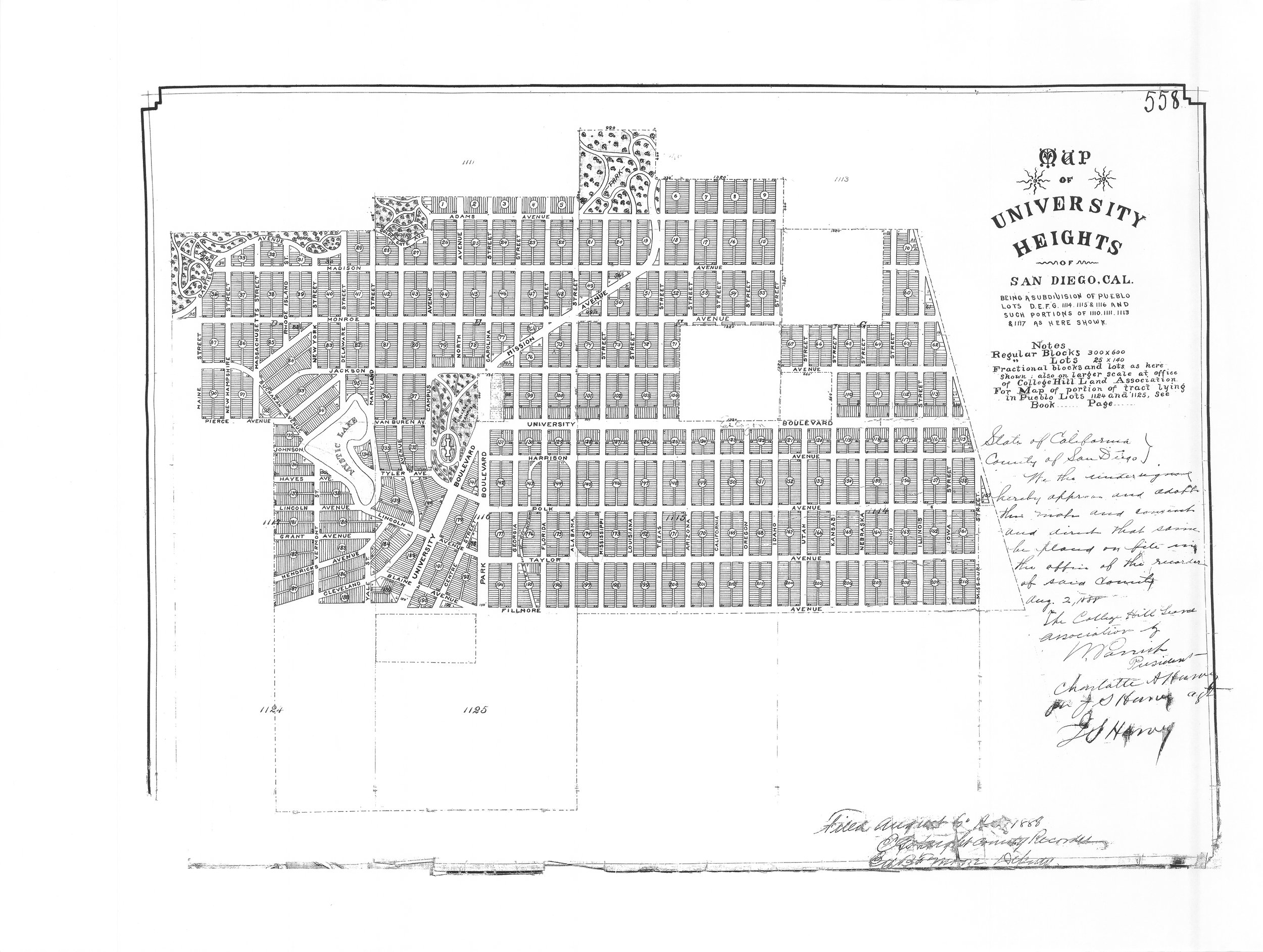

Planning in San Diego didn’t start until the early 1900’s. Before then, speculators and developers created their own plan for land they bought. A good example University Heights, which was planned and subdivided by the College Hill Land Association in 1888.

University Heights Subdivision Map 558, filed August 6, 1888

Urban planning in the City of San Diego began in 1903 when George Marston, founder of Marston’s Department Store, convinced the Chamber of Commerce to form a civic improvement committee. The committee hired John Nolen, a nationally known landscape architect, to give some direction to the unmanaged growth of San Diego. He created “San Diego: A Comprehensive Plan for its Improvement”, a 109-page study on the future of San Diego.

Nolen's recommendations were submitted in March 1908 and included grouping of public buildings; developing the waterfront into a recreational and transportation center; providing scattered playgrounds, and wide boulevards and avenues; and setting aside public beaches and regional parks.

“These recommendations may appear to present a heavy task for a city the size of San Diego," Nolen said in the report's conclusion. "Yet, after careful consideration and a comparison with the programs and achievements of other cities, I believe the proposed undertakings are all of a reasonable nature.”

Plan of Part of San Diego from “San Diego: A Comprehensive Plan for its Improvement” by John Nolen, 1903.

The city later hired Nolen again to prepare a “City Plan for San Diego” that was approved on March 8, 1926.

San Diego’s First General Plan Adopted in 1967

In the 1950’s, the city approved a Municipal Code change to add a zoning provision. This served the city until the first General Plan was adopted and ratified by the voters in 1967.

In 1974, with a grant from the prominent San Diego Marston family, planning consultants Kevin Lynch and Donald Appleyard produced Temporary Paradise? This groundbreaking study focused upon the natural base of the City and region and recommended that new growth complement the regional landscape to preserve its precious natural resources and San Diego’s high quality of life. Temporary Paradise? served as a major influence on the subsequent comprehensive update of the Progress Guide and General Plan adopted in 1979.

Proposed Street Plan in Existing Neighborhood from Temporary Paradise by Kevin Lynch and Donald Appleyard, 1974

The General Plan was again updated in 2008 and approved by a unanimous vote of the City Council. In June 2015, the Land Use and Community Planning Element was amended to include a “City of Villages Strategy” to “focus growth into mixed-use activity centers that are pedestrian-friendly, centers of community, and linked to the regional transit system.”

Community Plans Adopted for University Heights

University Heights is split down Park Boulevard between the Uptown on and North Park Community Plan Areas. Several community plans were approved for North Park affecting University Heights east of Park Blvd., including the 1969 North Park Commercial Area Plan, the 1970 Park North-East Community Plan, and the 1986 North Park Community Plan. The first Uptown Community Plan was approved in 1975 and updated in 1988, affecting the west side of University Heights.

In 2007, the Mid-Cities Community Planned District (MCCPD) was approved as part of the Municipal Code to further regulate land use in the Mid-City area, which included the area of University Heights east of Park Blvd. The MCCPD required residential buildings to include at least 5 architectural features from Contemporary, Spanish, or Bungalow styles.

Both the North Park and Uptown Community Plans were updated and approved in 2016 after several years of community input and collaboration with City planning staff to increase density in the older neighborhoods of North Park and Uptown while maintaining historic community character.

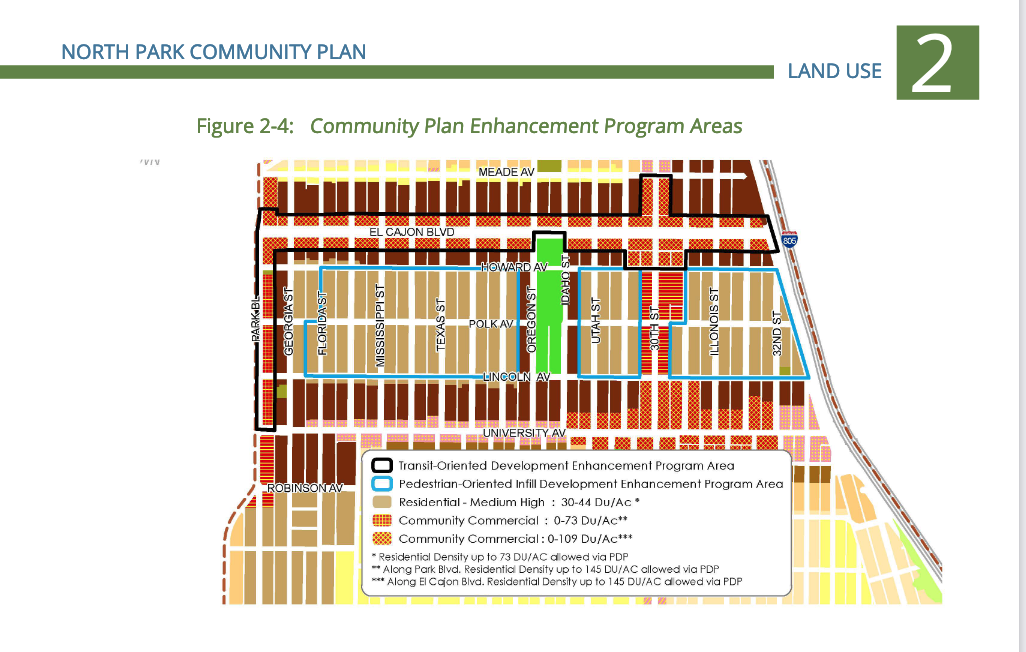

However, the Land Use Element of the North Park Community Plan update approved by the City Council in 2016 dramatically increased the allowable height and density of buildings along El Cajon Blvd. It also allowed for density bonuses of 33% above the normal zoning limitations in the “Transit Oriented Enhancement Program Area” and density bonuses of 66% in the “Pedestrian-Oriented Development Enhancement Area”.

Transit-Oriented and Pedestrian-Oriented Enhancement Program Areas, Land Use Element of the 2016 North Park Community Plan

The 2016 Uptown Community Plan update also suffered a similar fate. In a surprising and unexpected move on November 14, 2016, after 8 hours of City Council deliberation, District 3 Councilmember Todd Gloria made a motion to approve the Planning Commission’s recommendation to maintain the densities of the current 1988 Uptown Community Plan, eliminate the Mid-City Communities Planned District (MCCPD), and replace the MCCPD with the City’s new standardized zoning.

At their meeting on October 6, 2016, the Planning Commission maintained that the proposed 2016 Uptown Community Plan reduced the number of housing units in the Uptown area by 1,900 as compared to the 1988 Plan. However, Commissioner Hoffman felt that the 1,900 units were in areas related to airport safety considerations and would not impact the actual number of units.

These 2016 updates to the North Park and Uptown Community Plans essentially allowed developers to build projects with significantly increased densities and building heights in the North Park and Uptown areas with only ministerial review and “suggested” design guidelines.

An amendment to the Uptown Community Plan, called the Hillcrest Focused Plan Amendment, is currently in progress to increase the allowable number of units by at least 10,000 units within the Hillcrest area.

State Requirements Driving New Housing Construction

Both San the City of San Diego and California as a whole grew in population by approximately 6% from 2010 to 2020. State and local policy has evolved in response to the increased need for housing while striving to maintain or reduce Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions.

Since 1969, California has required that all local governments (cities and counties) adequately plan to meet the housing needs of everyone in the community. The state has produced a number of analyses over the years projecting housing needs called the Regional Housing Needs Analyses (RHNA). It describes the housing needs for Very Low, Low, Moderate, and Above Moderate household income levels, as shown below. These levels are based on Area Monthly Income (AMI) for a family of four, which was $75,500 in 2010 and $107,000 in 2019.

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

Household Income Limits for a Family of Four

Very Low Income, 0 – 50% AMI

2010 = $39,250

2019 = $53,500

Low Income, 50 – 80% AMI

2010 = $62,800

2019 = $85,600

Moderate Income, 80 – 120% AMI

2010 = $90,600

2019 = $103,550

Above Moderate Income = 120+ percent AMI

As shown below, housing production in the City of San Diego remains far below the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) goals for the 2010-2020 cycle. Only 48 percent of the total needed units have been constructed between 2010-2019.

Construction Starts in the City of San Diego by Income Level: 2010-2019, City of San Diego Housing Inventory Annual Report 2020

Further, the number of units affordable to Very Low, Low, and Moderate-income households fell short of the RHNA goals by 89%, while the number of units affordable to Above Moderate-Income households exceeded the RHNA goals by 7%.

According to the most recent RHNA analyses completed in 2019, the City’s target for the 2021-2029 period increased to 108,036 homes.

City Response to Need for New Housing

The City of San Diego has implemented a number of changes to the Municipal Code over the last decade to incentivize the production of new housing while attempting to maintain or reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Climate Action Plan Recommends Transit-Oriented Development

Starting with the City’s Climate Action Plan adopted in 2015, this plan recommended “transit-oriented development” near transit stops to reduce vehicle miles traveled. The 2016 updates to the North Park and Uptown Community plans codified these goals by offering density bonuses for development within Transit Priority Areas.

Municipal Code Changes Allow for Elimination of Parking

In March 2019, the Municipal Code was revised to allow for the elimination of parking in multi-unit buildings within Transit Priority Areas (TPA) to reduce the cost of construction. The cost for each off-street parking spot can cost anywhere from $50,000 to $90,000, depending on if it is above or below ground. As shown below, virtually all of Normal Heights, North Park, and University Heights are located within a Transit Priority Area.

City of San Diego Transit Priority Areas (in gold), February 2019

Developers Given Choice for Providing Affordable Housing

In December 2019, the Inclusionary Housing Ordinance was amended to give developers the option of paying an in-lieu fee or providing at least 10% of the dwelling units in a new residential development at rates affordable to low to median income households. The Ordinance was first adopted in 2003 to help the City meet its goals of providing affordable housing in a balanced manor.

Complete Communities Program Further Incentivizes Affordable Housing

In December 2020, the Complete Communities Housing Solutions Regulations were added to the Municipal Code, under the leadership of Mayor Kevin Faulconer. “The purpose of these regulations is to provide a floor area ratio-based density bonus incentive program for development within Transit Priority Areas that provides housing for very low income, low-income, or moderate-income households and provides neighborhood-serving infrastructure amenities.”

Simply put, the Complete Communities program will allow construction of a 6-8 story building without off-street parking within a Transit Priority Area (which includes almost all of University Heights) if the development includes the appropriate number of dwelling units for very low income, low-income and moderate-income households, and has an underlying zoning of at least 20 dwelling units per acre. Such a proposal would qualify for the following incentives:

Waiver of the maximum permitted residential density of the land use designation (in the Community Plan)

Waiver of the Maximum structure height

Waiver of the Development Impact Fees (DIF) based on square footage, rather than the number of dwelling units in the proposed development

Waiver of DIF fees for all covenant-restricted affordable dwelling units and all the dwelling units do not exceed 500 square feet, if the development provides a residential density that is at least 120% of the maximum permitted density of the applicable zone

An excellent article by KPBS reporter Andrew Bowen shows locations and examples of proposed and approved Complete Communities projects including the proposed project shown below on Adams Avenue at 35th Street in Normal Heights.

New State Laws Allow for Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs)

In addition to these local changes, the State recently passed Senate Bill 9 and Senate Bill 10 which allow for the construction of Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs) on single-family zoned properties.

Who Decides the Future of Our Older Neighborhoods?

Like many communities across California and the nation, San Diego has experienced a significant shortage of affordable housing over the last decade which is only projected to worsen over the next decade.

Starting in 2019, the City of San Diego has attempted to remedy this shortage by implementing a series of piecemeal, Municipal Code changes that often conflict with approved Community Plans, and bypass the robust review and input of the Community Planning Groups.

These code changes depend on developers to build affordable housing in the right locations, not on a thoughtful, comprehensive plan of action based on data and community input. This market-based approach has already resulted in the haphazard development of unattractive, unaffordable housing in our neighborhoods that is eroding the quality of life and sense of place for existing and future residents, and corroding public trust in local government to do the right thing.

In my opinion, the community plans for both North Park and Uptown need to be updated to include specific targets and possible locations for more affordable housing units, and be subjected to the thoughtful review and recommendations of the Community Planning Groups. Residents deserve the opportunity to shape the future of their neighborhoods, not to have it dictated by developers and City staff.

To paraphrase John Nolan in 1908 “when superb natural advantages and human enterprise are added to a sound public policy and a comprehensive plan of action (emphasis added), who can doubt the outcome?”

I would like to thank very much Kristin Harms for her excellent help in editing the article and her copywriting skills that improved the clarity and readability.